How to Embarrass Yourself on a Sailboat Full of Scientists Studying Microplastics

Lots of tour companies in Greece can take you out on a sailboat for a day – usually with sunbathing, cocktails and swimming stops. But instead of hopping on one of those when I visited the island of Paros, I found my way onto a scientific research trip, sailing its way through the Greek islands, collecting water samples to study microplastic pollution in the Mediterranean.

This is the story of what I learned in a day on that scientific sailing trip, how I almost ruined their research, and a few scientific debates I found my way into.

The crew of researchers and citizen scientists calling the sailboat home were on a two-week scientific vacation/ work trip around Greece with Sail & Explore.

My husband, Emanuele, and I joined the crew at the port of Naousa, on the island of Paros, for just one morning, and easily fell into the rhythm of their hands-on, science-vacation vibe.

Their work was straightforward: At certain locations, when the water was calm, they would pull out a trawler – a large device that, to me, resembled either a metallic manta ray, or something a farmer might attach to a tractor – and toss it overboard into the sea.

The trawler was adapted with filters to collect water samples that could only contain a certain size of particles, based on the size of the filter.

Those samples were then labeled and sent back to Switzerland. There, a lab would clean them (removing any natural materials using enzymes or other processes), filter them, and count the number of plastic particles.

(Click to enlarge and see captions!)

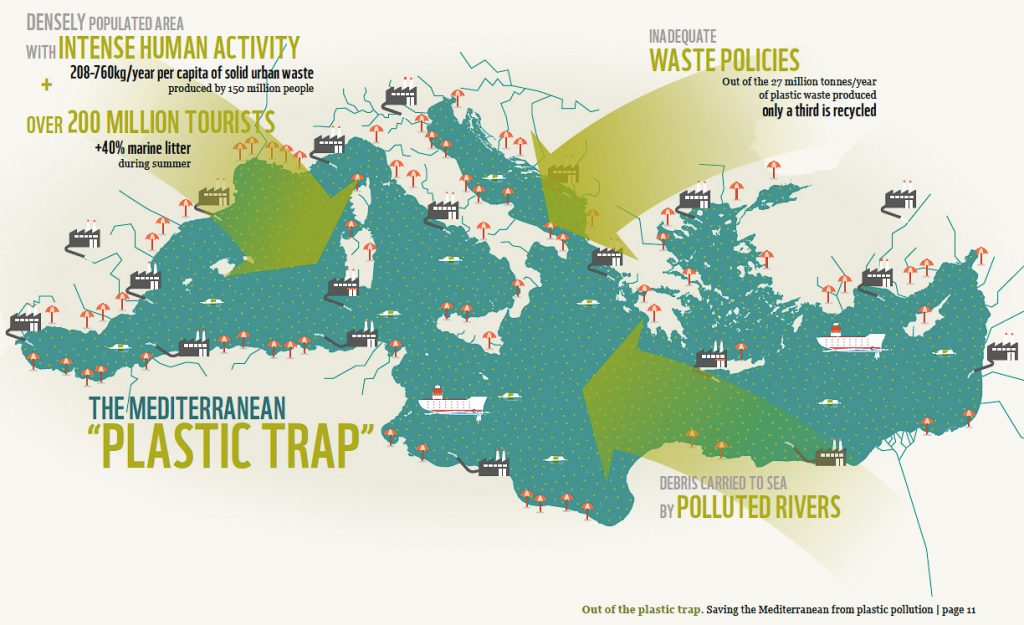

Of all the polluted bodies of water to choose from, the Sail and Explore expedition had good reason for being in Greece. The Mediterranean is one of the most concentrated microplastics areas in the world.

Why is the Mediterranean so polluted?

One big reason for all the microplastics pollution in the Mediterranean Sea is that it only has one inlet and outlet (the Strait of Gibraltar).

Plus, the region has a dense population, with 150 million residents around the Mediterranean basin, and tons of tourism. (200 million tourists visit the Mediterranean each year – leading to a 40% increase in plastic being dumped into the sea during the summer months.)

Add to that the unique geography that’s particularly good at stopping all those particles from flowing out to the wide-open Atlantic Ocean. (Think: The natural blockade that is Italy.)

Still, the water samples we collected on the sailboat that day looked fairly clean.

But the same location could be worse or better on a different day. Microplastics levels can vary by day, the tides, tourism levels, everything.

And, as our scientists and sailing crew began to explain, looks can be deceiving.

The Most Shocking Thing About Ocean Plastic Pollution

One of the scientific project leaders and co-founders of Sail and Explore is a Swiss researcher named Dr. Roman Lehner.

(Despite his academic pedigree, during the time I spent with him and his crew, the atmosphere was so laid-back that it would feel a tad inauthentic to call him by anything but his first name.)

Roman estimated there were 4 million microplastic particles per square kilometer in a sample they’d collected the week before, closer to Athens.

They’re still waiting for the numbers from the lab to confirm just how bad it was, but Roman said it was, “for sure one of the most polluted samples I’ve seen so far.”

That was between the port of Lavrio, and the island of Makronisos, as you can see on the map:

(Zoom out to see more, and click “List of Points” on the left for more info!)

And the shocking thing, as everyone on the sailboat crew – scientists and tourists, alike – told me, was that it looked like nothing.

What was possibly the most polluted part of the Mediterranean Sea – and thus, maybe the most polluted area of water in the world, in terms of microplastics – looked like perfectly clean water from where they sat on the sailboat, they said.

Just like where we were that day, off the Northern coast of Paros.

I had the same epiphany a few days earlier, when I’d helped Clean Blue Paros audit the plastic pollution on a local beach.

That beach also didn’t look terribly dirty, I’d thought. At least not compared with some truly tragic-looking stretches of coastline I’ve visited in Southeast Asia.

But after our crew of half a dozen people finished a couple hours of beach combing on Paros, this is what we’d collected:

Sometimes plastic pollution is obvious, but more often it’s hard to see.

That’s one of the things Roman said was most important for people to better understand: This problem isn’t limited to where we can see it.

In the Mediterranean and around the world, even water that looks clean is likely full of microplastics.

To illustrate the point, as we slowly motored around the sea (the boat’s main sail was being repaired at port that day), letting the trawler do its work, Roman told me about one of his research trips in the Whitsunday Islands. (Between Australia and the Great Barrier Reef.)

Along with local partners from the University of Newcastle, he did the first ever study of microplastic pollution in the area.

And there too, he said, the water looked perfectly clean.

But how much plastic you’ll find just depends on how small of a filter you use to look for it.

When the scientists put a trawler in the water with a filter to collect particles of 300 microns or larger, they found next to nothing.

Then they tried with a finer, 50-micron filter – and found 60 times more plastic particles.

The closer you look, the bigger the plastic problem is. As Roman explained later in an email:

“If you only sample in the “classic” way, down to 300 microns, you would assume that the waters around the Whitsundays are very clean. But if you have a deeper look into it, down to 50 microns, everything looks very different.”

Back on our sailboat in Greece, the expedition I was tagging along with was the first in the area to collect samples filtered down to 100 microns, instead of 300.

Roman said the data should be published by the end of 2022, so we’ll have to wait to see exactly what they learned. But it’s no stretch of the imagination to assume the Mediterranean could also be a lot more full of plastic than it looks. (And who knows what a 50-micron filter might find.)

Just when things had been going so well…

It was at about this point in our expedition that Emanuele decided it was time to put the drone in the air and capture some aerial footage of our outing.

He’d done this hundreds of times before, but almost always on solid land.

The boat was hardly moving at this point. Or at least that’s how it felt until the drone took off.

My memory of what happened next – just the next few seconds, really – has the slowed-down quality of when you think back on being in a dramatic event, like a car crash.

The drone’s four propellors started spinning. It went up a few feet to hover in place, as usual, its GPS locking in the position it started from.

But because that position was on a moving boat, the drone wanted to stay still, but the world around it kept spinning.

And I watched as our football-sized drone launched itself not just toward the water surrounding us, but first, toward the entire crew. It dove under the sailboat’s sunroof, bouncing toward the face of our captain as he ducked out of the way in shock.

And then our drone spun out sideways, landing with a plop in the water, right in front of the trawler collecting plastics.

But it didn’t go into the trawler – which is probably a good thing, as it would have ruined the water sample.

Instead, it sunk to the bottom, just one expensive, embarrassing piece of plastic to eventually be fished out of the sea. (Luckily, captain and crew handled it with grace.)

The Myth of the “Great Plastic Island”

Understanding the ubiquity of plastics – both drone-sized and micro – in the ocean should put to rest one overused analogy: The ‘plastic island’ concept.

It’s true that there are more dense agglomeration zones in the North Pacific gyre (between Los Angeles and Hawaii). But Roman pointed out that the idea of a “plastic-island” actually makes the problem sound simpler to solve than it really is.

If it were a dense accumulations of plastics like a real “island,” Roman explained, “then one could just easily collect it with a fishing net. People need to understand that the problem is ubiquitous and spread all over. It’s not just in one single spot, like an island.”

And the concentration of plastic pollution in the Mediterranean is actually 4 times higher than in the so-called plastic island of the Pacific.

And it’s getting worse by the year, not better.

But that might be changing. Luckily, more and more people are trying to quit plastic.

We’re changing our habits, and the items we buy, in order to avoid single-use plastics where we can. (That’s what a lot of my reviews on this blog are about.) And interest in plastic reduction is growing every day – I see it from the emails and DMs I get from readers, and from the small, sustainability-focused companies creating new innovations.

That’s one area where Roman and I disagreed, as I learned when we got into a friendly (but… intense) debate after several glasses of Greek wine at a dinner party with the Clean Blue Paros team.

To sum up the argument, my perspective was that changing our individual habits matters for two reasons:

- because we’re never alone. There’s no point in saying “I’m just a drop in the ocean,” because the ocean is made of drops. (Cliché, yes. But also, literally true.) Of course I won’t solve the problem as an individual using shampoo bars and every other kind of plastic-avoidance I’ve tested over the past couple of years. But I’m telling you about it. And eventually, you’ll tell your friends, and we’re all part of a growing movement. Of course we’re not yet at a critical mass to stop the plastics industry in its tracks, but we’re growing. And we’re putting pressure where it counts – which brings me to reason #2.

- because what we all buy sends a message to companies and to governments. That’s the beauty of capitalism – when it’s leveraged in support of an ethical cause, which obviously isn’t always the case. Voting with your wallet is just as important as voting.

Roman, on the other hand, said the plastics problem is too big for individuals to influence, and change has to come from the top down. It has to be massive and sweeping and it has to happen now.

Which I mostly agree with. Massive, sweeping and now would be wonderful.

And in his position as a researcher, Roman had, as he put it, “direct influence” on the Swiss government.

“Okay,” I said. “Then why hasn’t the problem been fixed yet?”

Well, that’s what I thought of later, that I wish I’d said.

Instead I bumbled through some argument about how, living in democratic-capitalist societies with free speech, we all have direct influence on the government and on corporations… you know, indirectly.

Democracy usually gets the job done, but it isn’t always quick, and it does require more than one lever of influence. Including individual actions, activism and market pressure. (AKA, what we choose to buy, what we reject, who we vote for, who we donate to, and how we speak up about it.)

But Roman said he still buys water in plastic bottles, when it suits him, because Switzerland has an 85% recycling rate for PET plastic bottles.

(That statistic is pretty accurate, from what I later read about recycling rates for at least that one type of plastic (PET) in Switzerland. But overall, the Swiss also use three times more plastic per capita than other Europeans, and recycle much less of it in total.)

[ Related: Here’s how I avoid buying plastic water bottles – even when traveling in places without safe tap water. ]

And that’s where the discussion got a little heated.

Look, I’m not a saint, and I don’t advocate for becoming one. (Look at the homepage of this blog. It literally says, “It’s not about being perfect – it’s about doing better.”)

A few of my sins:

- I don’t eat a completely vegan diet, even though, environmentally, going vegan is clearly the best choice. (But just cutting down on beef is a massive help for your carbon footprint.) Instead, I take Michael Pollan’s advice for eco- and health-conscious omnivores: Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.

- I’m not 100% plastic-free or zero-waste. (No, I can’t fit all my garbage for a year in a mason jar, and I’m quite skeptical that anyone can. I also do not have any desire to DIY my toiletries.)

- And I take several international flights in a normal year. (Although I am working on how to reduce my travel footprint.)

So, clearly I’m not perfect. But I am trying to improve on all of those fronts, and educating myself to figure out which areas are most worth improving, and which just won’t have a big impact.

Roman is probably right that buying a plastic bottle when it’s convenient really isn’t the end of the world.

Okay, he’s definitely right. It’s not the end of the world.

Especially if you live in a place like Switzerland where there’s a high chance your water bottle will actually be recycled. (And you make sure it gets into the right bin.)

But, as the old adage/meme says: One bottle isn’t the end of the world; one bottle a day for every person on the planet is.

So I’d just rather remove myself as much as possible from the part of the economy that creates the problem of plastic pollution. Instead, I try to spend my money with the companies that are part of the solution.

Anyway, I emailed Roman after the trip to ask if his take on plastic bottles was just the wine talking. Here’s what he wrote back:

“My take on the plastic is that one needs to understand what plastic exactly is. It is a carbon based material and carbon itself does not show any health issues/risks etc. The plastic industry is one of the biggest economical branches and we all are exposed to the material in our daily life.

At the end one needs to ask himself why do we have the problem? It’s because people litter all the plastics into the environment so people should start to better take care how they dispose the plastics at the end. It’s humanity and not the plastic!

Either you take care to recycle it or you put it in a proper trash bin. So to minimalize the problem we should push awareness, push the waste disposal management and for some materials exchange them with alternative (degradable) products.”

Well. There’s a lot to unpack there.

First, from my perspective, “It’s humanity, not the plastic!” sounds uncomfortably like the gun lobby’s platitude, “Guns don’t kill people, people kill people.”

Of course we should improve waste collection and recycling (many people around the world don’t have access to either). But those just clean up the mess once it’s been unleashed. So at the same time, let’s also stop creating the mess.

And sure, carbon doesn’t have any adverse health effects, but plastic is not just carbon.

And Dr. Lehner did publish a study that showed no immune response in the intestines (the non-human, model intestines) 48 hours after ingesting plastics. But scientists have known about other health effects of plastic for more than a decade, if not longer.

There are known endocrine disruptors in some plastics. (AKA, things that mess with your hormones. BPA and phthalates are two examples to check for on ingredient lists.)

And Roman is all too right that we’re all exposed to plastic and the plastics industry in our daily lives.

Earlier this year, scientists found microplastics both in human blood at shockingly high rates, and in our lungs. It’s too soon to know what health effects those may cause. Maybe the answer will be “None!” But somehow, I doubt it.

Roman is also right that the plastics industry is massive. And despite all the weight it could throw toward change, it hasn’t.

I’d rather not support industries that refuse to change, that lie to us about the false panacea of recycling to keep us buying their products, and shirk responsibility for the environmental crises that they’ve created and profited from.

But none of that was really my biggest point that I was hoping to make, while wine drunk and arguing about plastic bottles.

My point was that producing anything that involves a global supply chain to use just once, for just a few minutes, is wasteful, no matter how you slice it. Just as wasteful as, say, crashing a flying computer into the sea. Which I try to avoid whenever possible.

A huge thank you to Dr. Roman Lehner of Sail & Explore, and to the other researchers and guests who graciously shared their sailboat with Emanuele and me! (And gracefully dodged our drone attack.)

How to Join a Scientific Expedition for Your Next Vacation:

If you’re looking for a scientific vacation à la National Geographic, Sail & Explore might be right up your alley. Here are some more options:

- If you literally want National Geographic, Lindblad Expeditions runs the travel side of Nat Geo.

- Secret Paradise Maldives offers everything from day trips, to a 7-night Marine-Life Conservation Cruise, where you can help with marine biology research, learn about biodiversity and unique ecosystems, have the chance to snorkel with whale sharks, and experience local food and culture. (I’ve met the company’s founder, Ruth, and I feel confident in both the sustainability and the overall quality that I would expect from Secret Paradise.)

- Earth Watch is an international non-profit that lets you travel with more than 40 different scientific expeditions around the world, researching topics from climate change to biodiversity to plastic pollution.

- Natural Habit Adventures is a conservation- and wildlife-focused tour company that works with World Wildlife Fund to take travelers to remote destinations. (So not as much literally scientific travel, like Earth Watch, but science-themed. Also the first travel company to become carbon-neutral.)

(After spending some time with the captain and crew, I suspect the vibe of a Sail & Explore trip would be much more informal than traveling with these other, bigger companies, but that’s just my impression.)

- And if you’re just looking for a well-vetted, sustainable travel company to take a trip with, a few of my favorites are Byway, G Adventures, Intrepid Travel and UnCruise.

- Read the story of my UnCruise trip in Baja California (and use my discount code to save $$$ if you want to take a trip with them!)

- More about those companies in my Lazy Guide to Sustainable Travel, and this story about Alaska.

I don’t know how I ended up here, but I’m glad I did. Not only because it’s worth constantly being reminded of how bad the microplastics problem is, but because I likely would have made exactly the same mistake with the drone. It’s always slightly horrifying when you realise you only avoided doing something dumb by chance, so thank you for saving me from one more instance of that!