Confession: This Is My Carbon Footprint from Flights This Year [Part 2]

This is Part 2 of my series on joining Tourism Declares A Climate Emergency. This is the one where I calculate and share my carbon footprint from the flights I took in 2022. (Here’s Part 1. In Part 3, I dive into the details on several travel carbon calculators, and why I chose the one I did for this project.)

I have a confession to make: I’ve been putting off writing this post all year.

As you may remember, back in the fall of 2021, Tilted Map joined a travel-focused climate action group called Tourism Declares A Climate Emergency.

Quick refresher: Tourism Declares is a group of travel businesses that have committed to measuring and – this part’s important – figuring out how to reduce their carbon emissions. (They’re mostly much larger businesses than mine, with teams, or at least one specialist, dedicated to climate and sustainability. The tour operators Intrepid Travel and G Adventures are two of the most famous members, for example.)

The Part 1 article that I wrote at the time laid out the next steps that my declaration required, starting with calculating my carbon footprint from travel.

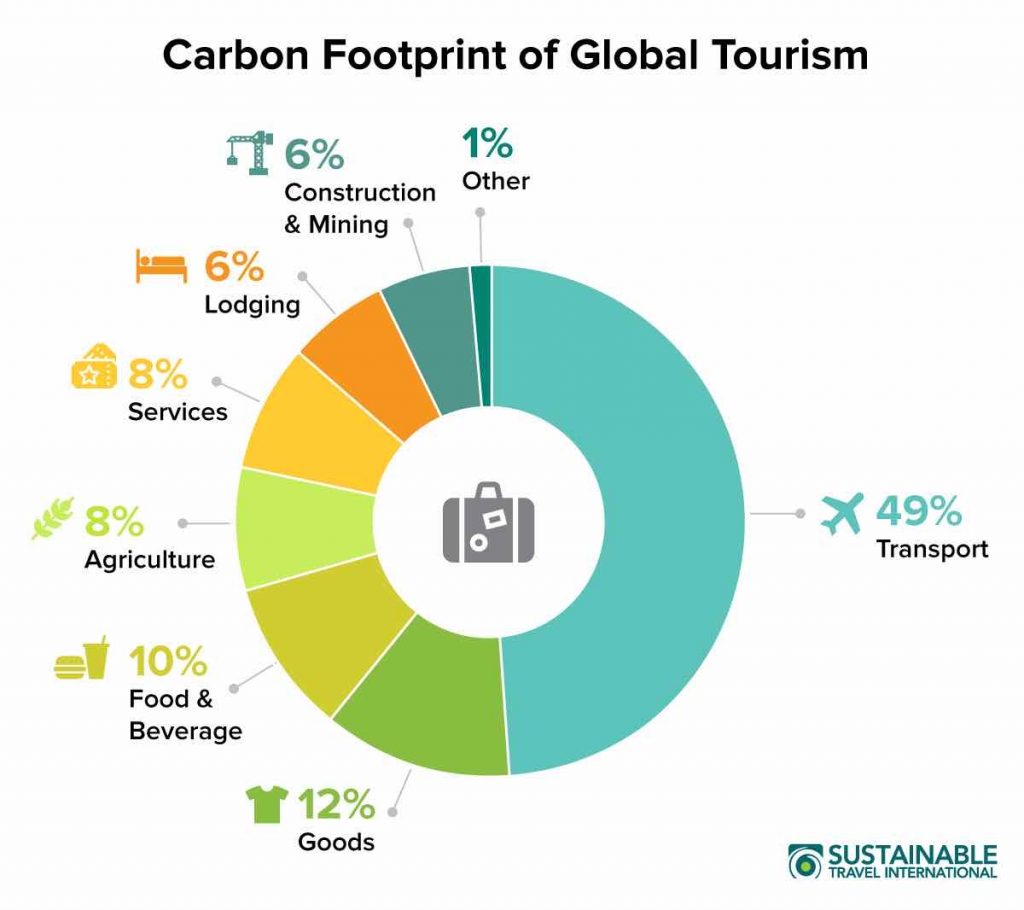

Since then, throughout 2022, I’ve been busy researching things – like the emissions footprint of the travel industry (about 8% of global annual carbon emissions), and of air travel (about 3% of global climate impact).

I also read up on the future of sustainable aviation fuel, and the validity of buying carbon offsets to compensate for flight emissions (here’s my take on that). I’ve listened to webinars, and pestered climate experts for one-on-one calls to answer my questions.

And I’ve traveled. A lot. But you’ve had radio silence from me on the actual next steps for my declaration. So now it’s time to face the music.

It’s time to take the scary step of calculating the carbon emissions from all my flights, instead of continuing to study how best to do so.

In theory, I should have gone back to 2019 (the last “normal” travel year) as a base year for my carbon footprint, but that felt about as relevant as going back to the 19th century. At this point, I’m back to traveling, and I have the rest of my year planned out, with my remaining flights already booked. So I decided to calculate my carbon footprint for 2022 as if all of it had already happened.

I also decided to only include flights in this calculation – not housing, food, trains, or other sources of carbon emissions.

This was mostly a practical decision, since the process for calculating emissions from flights is much easier than calculating emissions from everything else (thanks to the many simple travel carbon calculators that exist now).

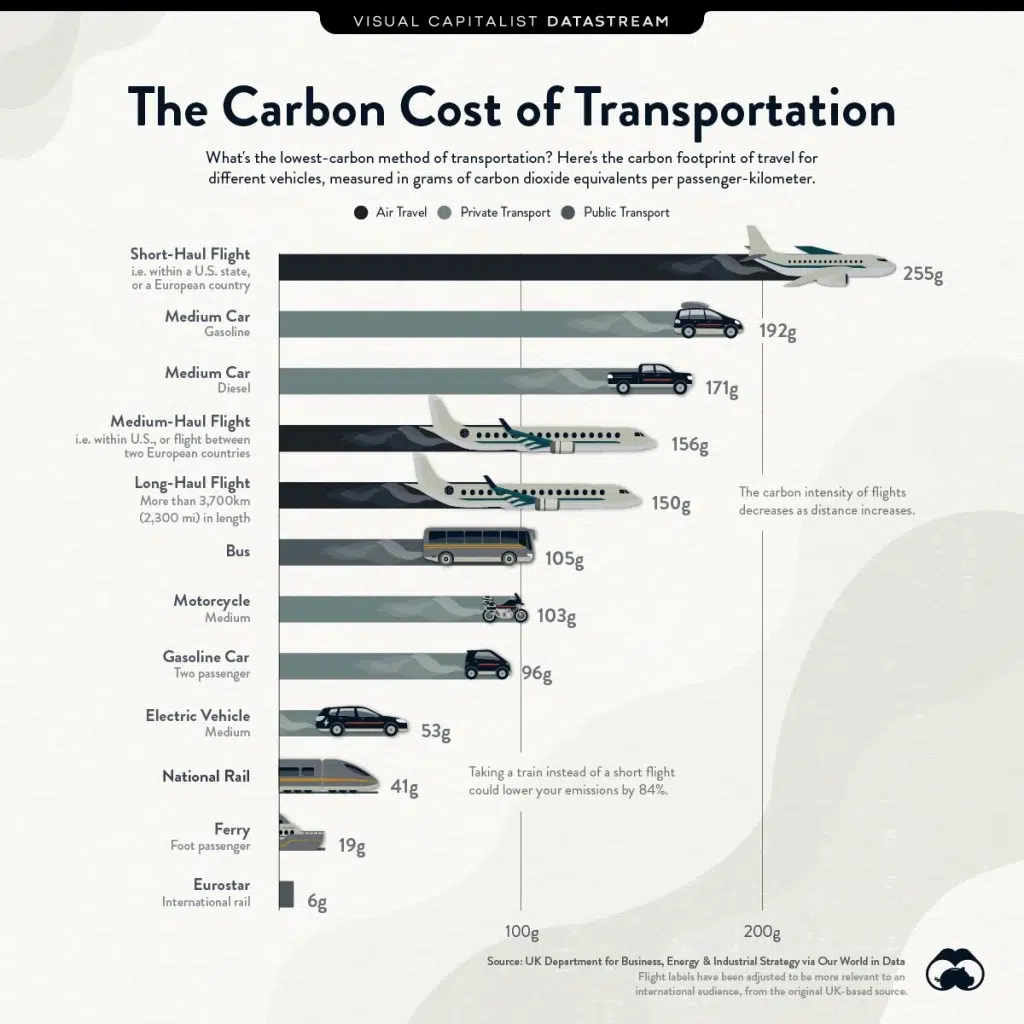

But it was also a choice that several of the climate experts I talked with recommended. That’s because flights are the lion’s share of most travelers’ carbon emissions – between 50% and 80%.

Flights are almost always the most carbon-intensive kind of transportation. And everything about travel that’s not flying – like eating food and living in climate-controlled buildings – I would be doing at home anyway.

(That’s not to say our carbon footprints from life at home aren’t significant or important. They are. But we can assume they’ll be similar whether we’re traveling or not. Flights are the biggest factor making travel more carbon-intense than the rest of life.)

And I took a lot of flights this year.

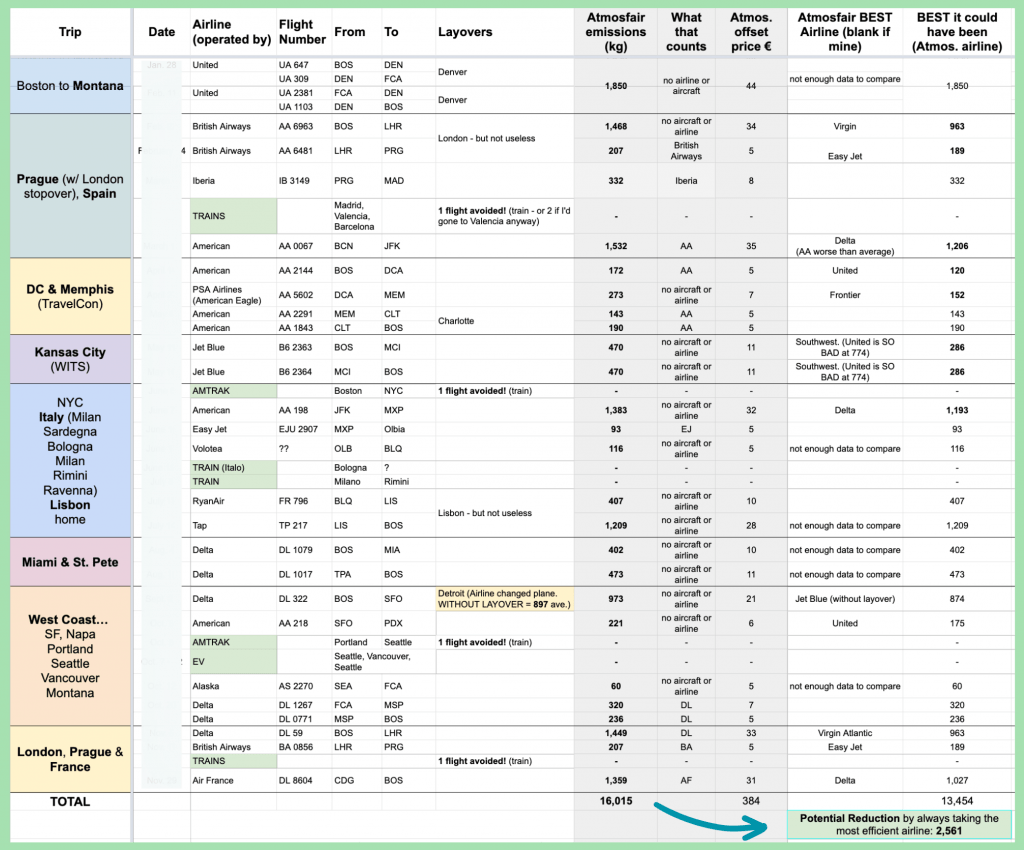

All told, counting business and personal travel (it’s a blurry line for me sometimes), I’ve taken 30 flights this year, passing through 23 separate airports. (Not 30 trips, but 30 individual flights.)

One of those airports, for the record, I’m filing under Not My Fault. I booked a direct flight from Boston to San Francisco, but at the last minute, Delta switched me to a route with a layover in Detroit.

A direct flight from Boston to San Francisco does exist, but the airlines had other plans for me. (We went for kayaking, visiting Napa Valley organic wineries, and a trip up the coast to Vancouver).

Counting that, only three of the airports I passed through were for useless layovers. The rest were starting points, destinations, or layovers that I stretched out into mini “stopover” trips to visit a city for 1 to 3 days. And I flew direct whenever it was an option (even when it cost more).

I also avoided four flights by taking trains. (Only counting routes where people often would actually fly, like Boston to NYC, and Prague to Paris. Not counting very short routes, like the town of Rimini, Italy, to Milan, for example.)

The Boston – NYC train, for example, emitted half the carbon of flying the same route. (34 kg of CO2 emissions vs. 72 kg. For the electric trains in Europe – vs. the diesel ones in the US – the difference was even bigger. To find this, I used TravelAndClimate.org.)

[Related: For more on why that calculator is best for trains and other kinds of travel, see my next post in this series, comparing travel carbon calculators.]

Okay, yes, I’m stalling with these anecdotes.

Without further ado, my carbon footprint from all those flights I’ve taken (and am still scheduled to take) in 2022 is… 16,015 kg of CO2 (or 35,307 pounds).

That’s 16 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions.

Here’s the spreadsheet I made to tally up the data:

I blurred out the dates, because I guess I still need some privacy..? (Click to enlarge & zoom if you want to dig in. The most interesting part is down in the right bottom right.)

That is… a staggeringly large carbon footprint. It’s just over 10 times the “climate compatible annual emissions budget for one person.”

(That’s how much we should each emit in order to limit global warming to “just” 1.5 degrees Celsius, which is the goal of the Paris Agreement.)

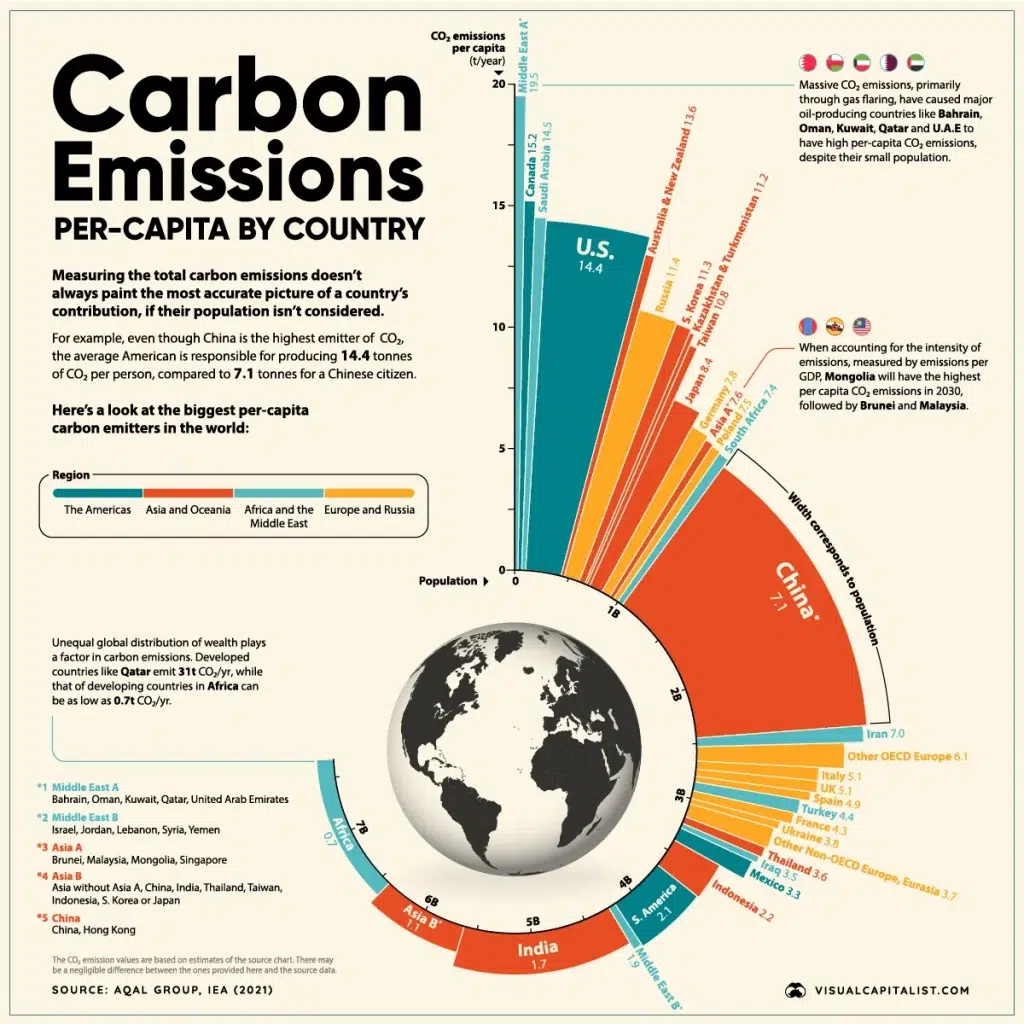

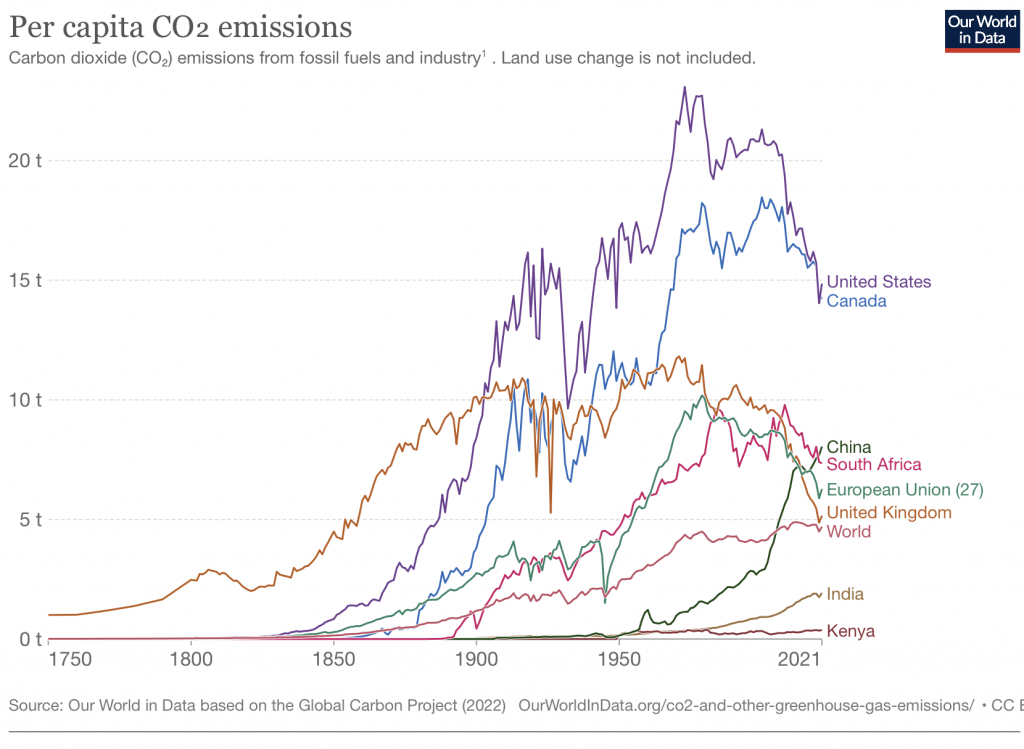

It also happens, ironically, to be about equal to the average annual carbon footprint of an individual in the US – which is already 5 times the annual average carbon footprint of a person in Mexico. (The annual carbon emissions per person in the US are 3 times higher than in France, Italy, Spain, or the UK. They’re double that of China, and 10 to 30 times an individual’s emissions in Ethiopia, depending on whom you ask.)

And I reached it just counting my flights.

Here are two interesting visualizations of the average carbon footprint per person, by country:

Yes, it’s true that I’m a professional travel writer, so my flight emissions should be more than most people’s.

And I travel to find ways for others to travel more sustainably, so theoretically I’m helping readers have a lower and more beneficial impact with their travel.

I have no idea how my carbon footprint might compare to that of other travel bloggers; I haven’t seen any other bloggers or travel writers share this calculation.

(If you know of other travel bloggers who’ve shared any part of their carbon footprints, please send me the links! Update: There’s at least one good one in the comments now, from my friends at Honey Trek.)

And considering that I eat mostly plants and very little meat, that I rarely travel by car, and that I live in a very small apartment and have chosen an electricity provider that uses 100% renewable energy, it’s safe to say that my flights probably are the vast majority of my entire carbon footprint.

But just looking at that number makes it impossible to avoid the elephant in the room: Travel has a huge impact on climate change. And if you care about seeing the world, you probably hate the idea of leaving it worse off by having seen it.

Why am I sharing this embarrassing fact?

Well, firstly and least importantly, because I got excited one day last year and I said I would.

Secondly, because, while calculating and reducing the carbon emissions of a travel blog is an entirely overwhelming and embarrassing thing to make a public commitment to, it’s pretty logistically similar to calculating and the reducing the carbon emissions of your own travel, as a regular person. So I’m hoping it’ll be helpful.

But most importantly, because the first step in reducing your carbon footprint is to figure out how big it is and where your emissions are coming from.

As I said in my first post on this topic, what gets measured gets managed. (I didn’t make it up; the management expert Peter Drucker did.)

And I learned a lot more from actually measuring my flight emissions than from just thinking about them and researching.

One big lesson from this is just how much of a difference the airline you fly on can make.

It’s often a 30% savings in CO2 emissions between the least and the most efficient airline. Sometimes it’s a lot more. A 63% reduction was the highest I saw in my own calculation – the difference between flying direct from Boston to Kansas City on United (the worst for this route) versus Southwest Airlines.

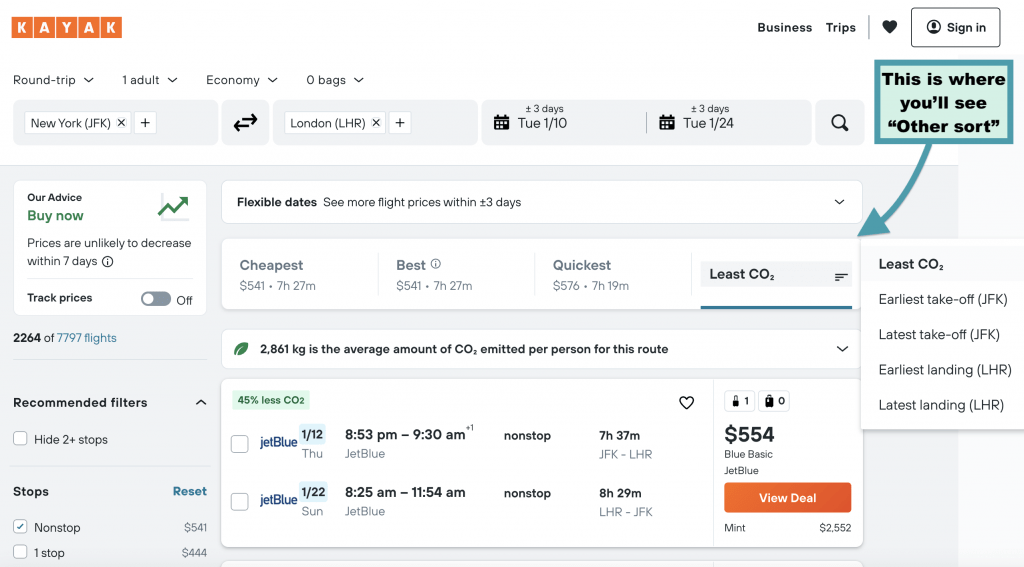

I’d seen this information before, from booking flights on Kayak. (Which displays emissions data from Atmosfair – the same data I used – if you ask it to.) But it really hit home when calculating the footprint for all of my flights at once.

UPDATE: Unfortunately, Kayak has removed the CO2 comparison feature from their search results. Skyscanner still has it though. Stay tuned for a guide to using it, coming soon.

This is a really easy way to reduce your emissions, without having to look at the actual aircraft you’re booking a ticket on, and sometimes it even makes more of a difference than choosing a direct flight over one with a layover. (That part really surprised me, but it very much depends on the route and the aircraft, so you have to check.)

And I did fly on the lowest emission airlines for all but 7 of my 30 flights this year. But still, I could have saved 2,561 kg of CO2 emissions if I’d always chosen the most efficient option. That would give me a 16% reduction in my overall carbon footprint from flights this year.

How to Calculate Carbon Emissions from Flights

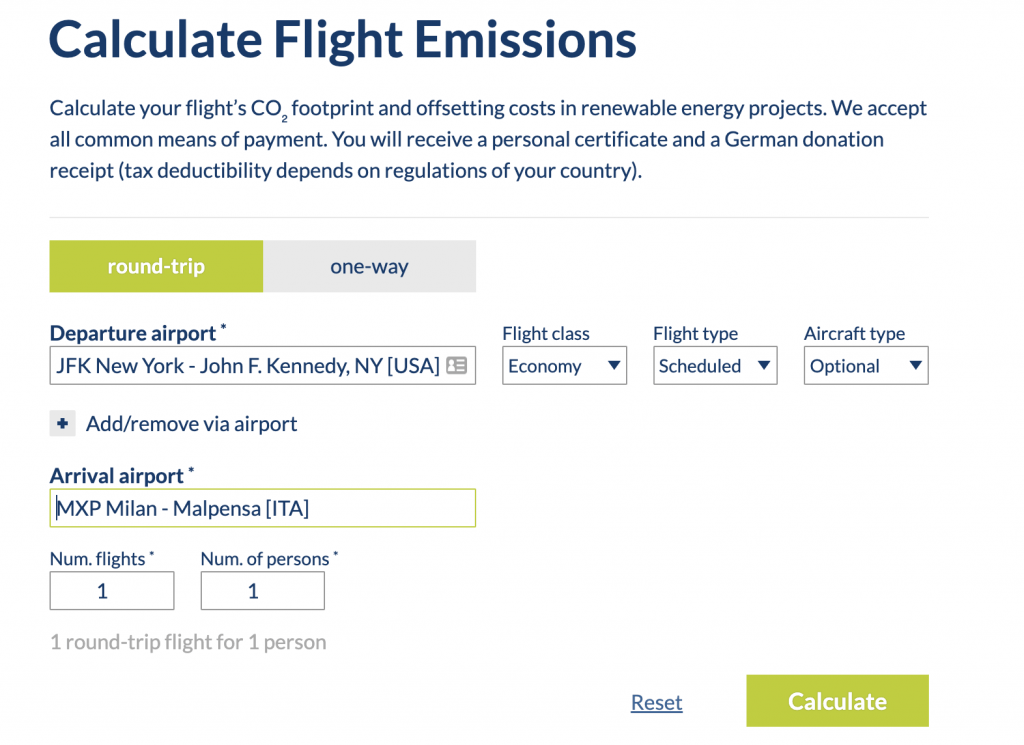

Wondering how I came up with that big scary number above? The short answer: I used the travel carbon calculator from Atmosfair.

The what from whom and why?

There are lots of free travel carbon calculators out there on the internet.

They all use slightly different methodologies, but all carbon calculators basically do the same thing: Take statistics that are well known to science – such as how much CO2 is emitted by a certain type airplane for every mile it flies, or a certain train for every mile it chugs – and make them accessible and useful to travelers through an interface.

You put in where you flew, and the calculator does the work for you.

I used Atmosfair’s flight carbon calculator, because it’s regarded as among the best. (It’s also a rather aggressive one, based on its methodology for calculating emissions. Other calculators would make my footprint appear smaller, but for now, the difference isn’t really worth worrying about.)

[Related: In the next article in this series, I compare several carbon calculators for travel, and what they’re each good for. Read that one, and you may understand it so well you’ll wish you’d never asked.]

But today, I don’t want to get bogged down in the details of calculations and methodologies. Instead, I just want to let this sink in a bit.

Because I write a lot about how sustainable travel is not a contradiction in terms. But frankly, seeing those numbers glowing at me from my computer screen makes that almost feel impossible.

Of course, there’s more to sustainability than the environment. (It’s a social and economic topic, too, about equity and fairness.)

And there’s more to the environment than climate change, as I’ve written about before (#14 here). But whether something is good or bad for climate change is a good proxy for many other kinds of environmental benefits or harms. (Like habitat preservation and biodiversity.)

Better travel — travel that’s less damaging, and more inclusive, with its social and economic benefits shared among more people, and profits directed to better causes — is of course doable. Easily so, in fact, compared with any kind of “carbon neutral” travel.

But I have to face the fact that I’m not quite in the 1% of greenhouse gas emitters, but I’m pretty close. (At least in terms of individuals.)

And as someone who believes in both science and personal responsibility – meaning that no, we cannot just hope technology will save us — how can I possibly go on like this? What can I do to reduce my carbon emissions from travel, besides just staying on the ground? Anything?

I’m going to break that down more in the next posts in this series, so stay tuned. (In the meantime, you can catch up by reading Part 1, or my Lazy Guide to More Sustainable Travel, for some non-overwhelming tips.)

Any thoughts on the topic, or questions about calculating your emissions from flights? Leave a comment below, and I’ll be happy to chat about it. This is a conversation we all need to be having.

Read Next: Here’s an update on this topic for 2023, about what I think is one of the most inspiring places to put your money if you’re a climate-conscious traveler.

This is super-interesting and very well done, Ketti! A lot of fodder for thought and discussion here.

Thanks a lot, Professor Woodruff! I have several more posts coming in this series. Need to break it up enough to make it digestible.

– Ketti

awesome read…thank you so much for the honest insights and for making us all think a little harder about the planes we choose to fly (something we have only recently started to do)

We have been tracking our flights + distance (we use an average tons/mile across planes) + carbon footprint (based on the average of a few different carbon offset models), and we offset (with a direct donation to RAN) every year. https://www.rtwpackinglist.com/our-flight-log/

i am sure we have missed things in a variety of places…but hey, it’s a start right? let us know if you have any suggestions for us!

That’s a fantastic idea, keeping track of ALL your flights over the years like that! I’ll have to start doing the same.

My first thought is definitely… uuuuugh it’s in pounds and miles. 😂 I wish we could all get on the same page for units, at least! Now that I’ve done this whole exercise in metric, I feel like I don’t understand the numbers at all in standard lol.

Anyway, I’m glad you mentioned offsetting with a donation to RAN. I’m working on another post about offsets (and alternatives to them), so that’s an interesting idea. I’d love to hear why you chose them.

Cheers,

Ketti

I fly at most 2 times a year, so how to calculate carbon emissions?

My suggestions for some good, more wholistic, “personal footprint” carbon calculators are at the end of the next post in this series.

Hope that helps!

Ketti

At the moment, everyone needs to make their own judgments on how to deal with the issue. Until systemic changes happen (which is urgently needed, but apparently not a priority of our governments), it’s up to individuals. My own way of dealing with it is this:

1) I no longer curb my flying very much. I’m an aviation enthusiast, have been since childhood. I absolutely support rules changing, flying becoming rationed, more expensive or progressively more expensive for frequent travellers, or even banned for short routes. I’m all for XR and Letzte Generation and Just Stop Oil causing a ruckus, and all for governments changing rules to change our ways of life. But as an individual, I know my own decisions make an infinitesemal impact, and even the collective decisions of all green-minded people make only a marginal impact. It seems utterly pointless to avoid doing one of the few things that I enjoy unless the rules change so collective habits as a whole change.

2) I bite the cost-bullet and pay for 100% SAF for an economy seat’s share of the flights I book. I use either http://www.compensaid.com (Lufthansa Group’s platform) or https://www.flyonsaf.com (Chooose’s platform, which powers SAF purchases for several airlines and is a bit cheaper than compensaid). This makes flying much more expensive for me, and implicitly reduces the number of flights I can book in a year. But more importantly, I clean up the impact of my own bookings, up front and instantly. Not with an offset that might or might not take CO2 out of the air over several decades, but by ensuring my share of my flight’s fuel was made from CO2 that was taken out of the air before I took off.

One way I think of it is comparing flights to dog ownership. If I wanted a dog, one might argue against it based on the dog pooping on roads, in parks, in children’s playgrounds. Flying and doing nothing is like letting the dog poop everywhere and walking away, leaving the problem for someone else. Flying and paying the pennies for a CO2 offset is like letting the dog poop and voting for whichever party promises to deliver more frequent street cleaning services in local elections, thereby saying “well, eventually it’ll be cleaned away, and I did my bit to ensure it might be cleaned away sooner”. Flying and paying for SAF is like walking around behind the dog with one of those plastic bags, collecting its poop and disposing of it in a bin – i.e. cleaning up the mess I cause by my selfish decision to own a dog. It’s the least I can do.

Incidentally, paying for SAF also means that flying on some (intra-European) routes becomes comparably expensive to taking a train in some reasonable level of comfort (sleeper cabin rather than couchette on night train, first class on long distance daytime trains, etc.), so I try to satisfy at least some of my wanderlust cravings by rail.

I am a bit wary of the Atmosfair calculator. As far as I know, gruenerfliegen.de uses theirs, and they have some phenomenally silly results. I repeatedly let them know about problems and miscalculations, but they only ever fixed the most egregrious one (when the calculator produced a result suggesting flying from Germany to Spain via two intercontinental stopovers halfway around the world had a 90% smaller footprint than flying nonstop). The most common errors, they never fixed: the calculator will assign different CO2 values to the same seat on the same flight, depending on which airline is nominally on the ticket. So if one flight is sold as many different codeshares, the calculator will tell you booking it as LH#### is much more efficient than booking it as TP#### or UA####. This is utter nonsense (the plane does not use more fuel if you have a different number on your ticket), but it’s deeply embedded in their algorithm. It tends to favour Lufthansa, for some reason (atmosfair being German might be a factor…). So whenever you see it recommending one flight over another by up to 20% or so, this can be often the result of incorrect biases and assumptions.

Hi Robert,

Thanks for your comments, lots of interesting points in there! You’ve touched on a lot of topics that I’m in the midst of researching for upcoming articles.

I definitely feel like I know where you’re coming from about being an aviation enthusiast and not curbing your flights anymore. I’m sort of in the same boat as a travel writer. In addition to it being my career, this is my passion, and while I personally end up traveling a lot, my job is writing about how other people, who travel a lot less, can reduce their footprints and support smaller, more local, and more sustainable businesses in ways they might not have known about.

I may be biased, but I think it’s a useful project.

But I definitely do look for alternatives – trains as you mentioned, and comparing other modes of travel, which I mostly do using the Travel And Climate calculator (more on that in this post). I think that’s the least we can all do.

Thanks for the tips about how you purchase SAF. That’s one of the ideas that will be in my post about carbon offsets (and alternative ways to invest), so I’ll definitely look into the two you sent.

As for Atmosfair, I’m hesitant to think that they’re favoring German airlines. Their methodology is quite transparent (as I jus wrote about in the same article linked above).

For the codeshare differences, do you mean when looking at Atmosfair data on Kayak or Momondo? (Since there are no flight numbers shown directly in Atmosfair.) I just did a few searches looking for that and haven’t noticed it, but I would be curious to see some screenshots if you see it again and want to email them to me.

One thought is that these differences could be related to average load rate (as some airlines are better than others at filling seats). Maybe their algorithm doesn’t know how to differentiate between an airline actually flying the flight (and thus choosing the aircraft), versus just adding their name via a codeshare. I’m not sure, but I’ll add this to my long list of questions that I’m hoping to ask them in an interview (if they’ll ever reply to my many emails!).

Thanks again for your thoughts, Robert, and keep in touch!

Ketti

Hi Ketti,

This is all very interesting, since I’ve been thinking about how to reduce travel emissions for quite a while. Your work.is among the most extensive I’ve seen on this topic

My thinking has resulted.in a travel planner website, one that mixes different travel modes and lets you order alternatives by CO2 estimates.

Say for instance that you want to travel from Missoula in Montana to Boston. It may then suggest that you travel overland to Bozeman and fly direct to Newark..From the airport you have a direct train to Boston.

The CO2 calculations for this assumes electric train and diesel operated bus. There is by default no adjustment for non-CO2 impacts from aviation,.but you can choose a CO2-multiplier in the sidebar menu.

Within Europe this admittedly works better, since plenty.of schedules are openly available. It is nice to see at what times suggested connecting trains run.when picking a flight.