So Big Cruise Ships Are Bad for the Environment… But Why?

This post is a simple overview of the biggest sustainability problems in the cruise industry, why exactly cruise ships are so bad for the environment – and some solutions. (All from interviews with experts.)

Among other foiled travel plans for 2020, I had scheduled a dreamy sounding trip to Mexico with UnCruise, a company that bills itself as a sustainable alternative to big-ship cruising.

So I started researching: What does it mean to be an alternative to cruising? An alternative to what, exactly?

For starters, what I had planned with UnCruise was to be a week-long sailing trip in a small corner of the Sea of Cortez. The menu was based on sustainably-caught, local seafood, and farm-to-table (or farm-to-boat) fruits and veggies. There were going to be shore excursions for interpretive desert hikes and horse-back rides among the cacti of Baja California.

Everything was going to be included (no up-charges). And there would have been 100 people on the boat (30 of them crew members). Sounds like a dream, right?

Update: If you’re considering an UnCruise, I now have a pretty cool discount to share with Tilted Map readers! Use my code TILTED500, to save $500 per person on your trip!

I’ve never been on a “normal” cruise, but I’ve read a lot about them. And this didn’t sound anything like a cruise.

If you keep up with the sustainable travel world, you know it’s sort of a trope to hate on big cruise ships.

We know cruise ships are dirty. We know they pollute… but how, exactly? And how much? Is cruising really as bad for the environment as they say?

That’s what I wanted to learn before my “alternative cruise” trip. But, 2020 being what it was, of course the trip had to be pushed back.

But I still want to share what I’ve learned about pollution, environmental problems, and sustainability in the cruise industry.

(I’m hoping to reschedule my trip with UnCruise in 2021… or 2022. And of course I’ll report back on how it goes!)

UPDATE: This trip was indeed pushed back – three years! But I finally did get to explore the Sea of Cortez with UnCruise in February, 2023.

I originally published this article on sustainability in the cruise industry in October, 2020. I’ve now completely updated it in March, 2023.

Is There Such a Thing as Sustainable Cruising?

UnCruise supposedly offers a sustainable way to travel. Or at least a more sustainable way to cruise. Which, according to 99% of what I’ve heard and read about the cruise industry, doesn’t set the bar very high.

But there are better and worse ways to do everything. That’s one of the founding ideas of Tilted Map – sustainability is a spectrum. We don’t have to do things perfectly for it to be worth improving.

But can one company can be meaningfully different, especially in such a dirty industry? After a long time researching sustainable businesses, I’m 100% sure that the answer is YES.

For example: Do reusable Q-tips and shampoo bars really make a difference in how wasteful our toiletries are? Do electric cars really make a difference in the climate impact of driving?

And is UnCruise really more sustainable than any other cruise company on the high seas?

To answer that question, I need to establish a baseline (what is normal for sustainability in the cruise industry? What are the problems?) so I can understand if any one company is doing better than the rest. This article will be that baseline.

And in another post soon, I’ll get into what UnCruise does differently.

[Related: How to find more sustainable hotels anywhere you travel.]

Why Cruise Ships Have a Bad Environmental Reputation

It’s safe to say cruise ships are the worst polluters in the travel industry. There are lots of reasons for that, but one of the biggest is the fact that they’re not really regulated at all. They do whatever they want, and rarely does anyone stop them. (Yes, cruising is worse for the environment than flying, even. That’s both because of their carbon emissions, and because they get away with doing everything I’m about to describe.)

Entire books have been written on this topic, but to summarize, these are the major sustainability failures of cruise ships:

The most infamous is probably dumping grime into the ocean – both untreated sewage and oil. Yep, directly into the sea, usually under the cover of night, while falsifying documents to lie about it. (Royal Caribbean and Carnival have both been fined millions for this.)

But even worse is that cruise ships burn really dirty diesel fuel, including when they’re docked at a port. (The fuel is much worse that what’s used in cars. More on that below.) This releases tons of greenhouse gases and creates air pollution in port cities that makes them more toxic than some of the most polluted cities in the world. (Of course, they create the same pollution out at sea, and it’s not like it leaves the planet. But it’s most noticeable at port.)

Who’s Reporting on Cruise Ships’ Sustainability?

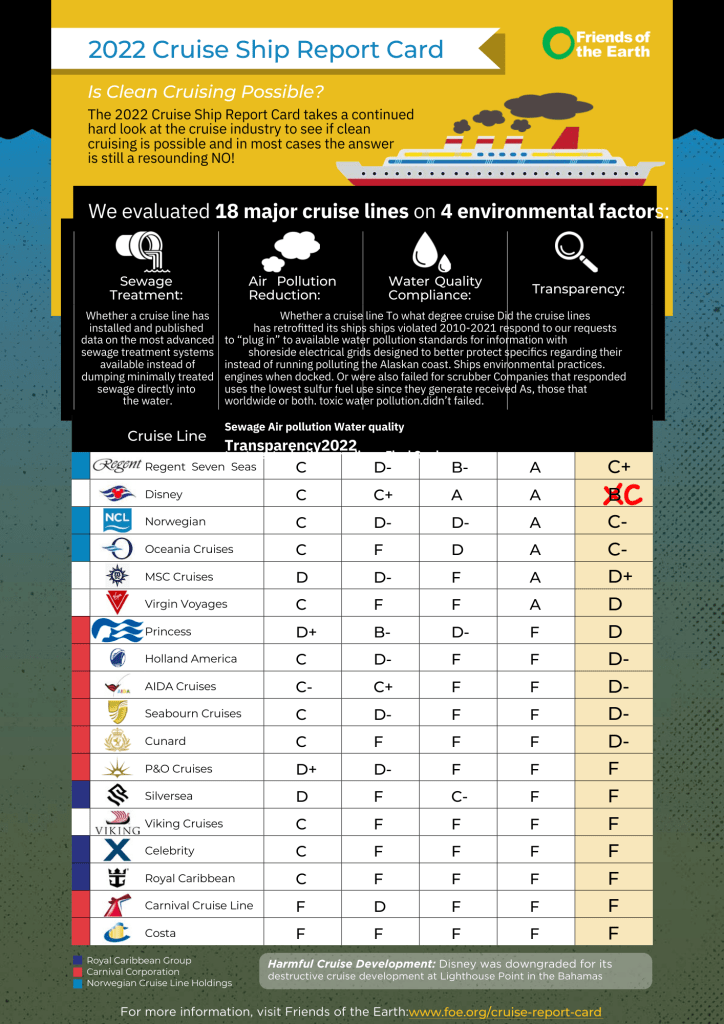

An environmental group called Friends of the Earth (FOE for short) writes a detailed “cruise report card” every year, ranking the big cruise companies from cleanest to dirtiest.

The three things I just mentioned are the main factors in the report card: How well they treat sewage, where they dump it (and if they do so legally, which many don’t), and what they do to minimize air pollution. (The fourth factor FOE considers is whether or the not the companies are transparent in replying to their questions.)

Shout out to the experts: A lot of the info in this post is from conversations I had with two very helpful cruise ship experts at FOE – John Kaltenstein and Marcie Keever. (Marcie is FOE’s Legal Director, and Director of the Oceans and Vessels program. John is that program’s Deputy Director.)

Here’s their 2022 cruise ship report card. (UnCruise isn’t on it, so I asked Marcie why. She said it’s because it’s too small of a company. UnCruise’s closest competitor that is on the list is Viking Cruises – and they didn’t do well.)

And here you’ll find every report card, starting in 2009. You can also look up the performance of specific ships – because they’re all different, even when they’re owned by the same company.

After reading through those, I picked Marcie and John’s brains so I could sort out – in plain English – what the ratings in their cruise report cards actually mean about the way the cruise industry works. Here’s an overview of the problems:

Cruise Ships and Sewage

Ugh, I hate to start with the gross and surprisingly complicated part, but it’s important.

The sewage issue is really about two questions: How well ships treat it (if they even do treat it), and where they dump it.

Sewage Treatment on Cruise Ships

FOE ranks how well ships treat sewage based on whether or not they’ve installed the latest “advanced sewage treatment systems.” There are two kinds of sewage: “black water” is from toilets; “gray water” is everything else – from laundry, dish washing, sinks and showers. The treatment systems are for both because, as John told me, around 95% of a ship’s sewage is gray, and gray water can be as toxic as black water, with similar polluting nutrient and bacteria content.

When they’re dumped in the ocean, those nutrients and bacteria cause oxygen depletion, and toxic algae blooms – which cause ocean dead zones. And they spread bacteria and viruses, which means anyone eating seafood from areas where cruise ships have dumped can get sick. Plus… gross.

But if ships do proper treatment, with advanced systems, then the “sewage” water they’re dumping is cleaner than the tap water in most US cities.

(Although it still could have other problems, like containing metals that kill baby salmon in Alaska.)

John also said the “non-advanced” systems are pretty rudimentary and don’t do much at all. Yet only about 60% of cruise ships have the advanced treatment systems. That’s some progress, but John said there’s no excuse for it not to be 100%.

“These are billion-dollar-plus ships – this is a small fraction of the cost. Considering the harm sewage can do, and the pristine nature of a lot of the places these ships are visiting, it’s kind of shameful that they’re not all equipped at this point.”

John Kaltenstein, FOE

Sewage Dumping (The Really Gross & Complicated Part)

Yes, cruise ships dump raw sewage directly into the ocean.

Want to know the even more shocking part? If a ship is more than three nautical miles from the US coastline, that’s actually legal. It’s allowed to dump ANY sewage, WHEREVER it wants.

That means cruise ships regularly dump hundreds of thousands of gallons of human waste. The biggest ships can carry 9,000 people, and all of their untreated sewage is dumped into the ocean, just three miles from land. (Three nautical miles = 3.5 normal miles, or 5.5 km.)

It’s complicated because the rules depend on the country and state. Three nautical miles is the general rule in the US. Some countries extend it to 12, but with even weaker treatment standards, and often with no enforcement. (And most countries don’t have any regulations for gray water treatment or dumping. But remember, gray water is just as toxic as sewage, or “black water.”)

Even after researching that, I just couldn’t believe it was possible. So I checked it with Marcie. She confirmed:

“This is true – there are no rules in the US beyond three nautical miles, except in a few places like the National Marine Sanctuaries in California and all of Puget Sound, Washington, for example.”

Marcie Keever, FOE

Plus, 97% of cruise ships break the laws, anyway.

Carnival Corporation is currently on criminal probation – again – for repeatedly dumping raw sewage and systematically lying about it. (And Carnival Corporation is the biggest player in the industry – they own Princess Lines, Holland America and many others. All have been found guilty of felony counts of deliberate pollution for dumping both plastic and sewage into the ocean.

This is why it’s so important that cruise companies install (and actually use) the right treatment systems.

(You’d think that using the system would be a given, after installing it, but a whistleblower from a Princess cruise ship reported that it had a “magic pipe” installed to bypass the system.)

If the cruise companies would simply treat their sewage properly – with an advanced treatment system – then it wouldn’t be nearly as big of a deal where it gets dumped. (Because it would basically be tap water.)

But if they don’t want to do proper treatment (hey, it costs money), sadly, all they have to do is go a few miles from shore to legally dump it. Yet they often don’t bother to even to do that! Instead just dump the sewage illegally, closer to shore.

It’s kind of amazing – there are so many opportunities for cruise companies to do the right thing, but just keep choosing to be terrible polluters, instead.

Alaska has the strictest regulations in the world for cruise ships and sewage.

That’s why complying with Alaska’s rules is one of the categories that FOE grades cruise companies and ships on. If a company applies for a permit to dump sewage within three miles of Alaskan shore, then they’re graded on whether or not the Alaskan government cited them for any violations.

But the problem is, if they just don’t apply for a permit, and dump their sewage further from shore, then they’re excluded from this grading category. But they’re still doing huge environmental damage. These are delicate marine ecosystems that didn’t evolve to have tons of human waste dumped on them.

Recommendation:

If you want to read more about how the cruise industry really works, plus an overview of the tourism industry as a whole that will really make you think, Elizabeth Becker’s “Overbooked” is a classic on sustainable tourism.

Air Pollution from Cruise Ships

You made it through the confusing part! The air pollution from cruising is simpler than the sewage stuff (and there’s less complex regulation).

Still though, there are three parts of the air pollution problem:

- Cruise ships burning very dirty diesel fuel (way worse than what goes into a diesel car).

- Ships using “scrubbers” to cheat the regulations on burning that extra-dirty fuel.

- And whether or not ships plug in to shore power – which lets them avoid burning the dirty fuel while they’re docked at port.

The basis of all these problems is the diesel engines that power most cruise ships. (Some ships run on LNG – liquified natural gas – which is cleaner for air pollution, but actually worse for greenhouse gas emissions.)

Cruise Ship Fuel = the Dirtiest Diesel Around

Dirty diesel fuel is what Marcie said is the worst sustainability problem with cruising:

“Their fuel is thousands of times dirtier than truck fuel. It’s really the biggest problem with the industry right now.”

Marcie Keever, FOE

Read that again – thousands of times dirtier than the diesel fuel used on land.

The filthy fuel (called marine gas oil) means the big diesel engines on cruise ships emit tons of toxic smog that people on board and in port cities have to breathe.

And while the smog is the most obvious in port, cruise ships also emit tons of greenhouse gases. (Cruising is actually worse for the climate than flying. I feel like I fully understand how much that’s saying, after I looked into my carbon footprint from flights last year.)

This might make you wonder: How clean is the air when you’re on a cruise? And the answer is not very. It’s at least as toxic as in the most polluted cities in the world.

Smoke Stack “Scrubbers” = Another Cruise Industry Scam

“Scrubbers” are an expensive way of turning cruise ships’ air pollution into water pollution.

They’re like filters that theoretically clean the bad stuff out of exhaust fumes as it comes out of a ship’s engines. (Imagine holding a wet sheet over a campfire. It would collect all the tiny pieces of ash that the smoke carries up into the air.)

“They’re basically taking an air emission problem and making it a water problem.”

John Kaltenstein, FOE

International laws for marine fuel were strengthened in 2020. They now require cleaner fuel, with lower sulfur content. That’s great. But ships can just install scrubbers and be excused from following the laws. (And get out of buying the cleaner, but more expensive, fuel.)

The problem is most cruise ships clean their scrubbers with sea water – and often just dump that dirty filter water right back into the sea. Marcie described it as, “acid sludge and waste water that are incredibly damaging to the ocean environment.”

Shore Power for Cruise Ports = A Bit of Hope!

When a cruise ship (or any ship) is parked at port for a day, it keeps its engine running to provide electricity for everything on the boat. As we’ve been discussing, that’s often a very polluting diesel engine.

Have you ever waited at a stoplight with your windows down next to someone driving a diesel truck? (I’m from Montana, so I have.) If not, you’ll have to imagine: The engine is so loud it’s hard to hear a conversation. And the exhaust smells toxic (which it is) and leaves a visible dark cloud in the air.

“Shore power” is a simple solution to this kind of cruise pollution: Cruise companies retrofit ships to be able to “plug in” to electricity from land when they’re in port. And voilà! They can turn their engines off.

Literally, these systems look like gigantic wall plugs. And cities design their ports (and pay) to include “outlets” for cruise ships.

But of course, you can see where this is going to go south, right? The cruise companies have to also install the “plugs” on their ships.

It has been done really well in some cities and on some ships – so we know it’s possible. Sometimes cruise companies (shockingly) have even helped cities pay for shore power. (As Princess Cruises did with the city of Juneau).

But most ports still don’t have shore power. And since it’s not there, most cruise companies haven’t set up their ships to connect to it… Or is it the other way around?

Brooklyn is the only port on the East Coast that has shore power access. Out of about 30 cruise ships that dock there in a (non-pandemic) year, only half of them hook up to the cleaner shore power, which is totally absurd.

Even worse is that the Manhattan cruise terminal gets 180 ships a year, and has zero shore power. Charleston gets 100 ships a year and also has none.

When we were discussing the situation on the East Coast, John put it bluntly:

“Carnival made a little over 3 billion dollars in profit (in 2019). This is the west side of Manhattan – there’s no reason there shouldn’t be shore power.”

John Kaltenstein, FOE

Several European and Chinese ports are adding shore power for cruise and cargo ships. (China actually said it would require every cruise ship that has the hook-ups to use shore power by 2021, and would require cleaner fuel. But I haven’t been able to find any evidence that’s actually happened.)

San Diego expanded its shore power this year. Tiny Malta is doing it. And Juneau, Alaska, has had shore power since 2001.

But most of the US is way behind – maybe because everyone’s bickering over who should make the upgrades first. For example, Miami – obviously a massive hub for cruise ships – recently redid their ports without adding any shore power hook-ups. But now, they’re aiming to have the world’s largest shore power system by the end of 2023.

Cruise Ships and Climate Change

Greenhouse gas emissions in travel are whole monster of a topic (which I’ve been writing a whole series about, since I joined Tourism Declares A Climate Emergency). So I won’t go far into this, but I have found some alarming research.

A rough calculation by the International Council on Clean Transportation (a very reliable and unbiased source) found that a cruise emits at least twice as much carbon as a vacation on land. And that’s for the most efficient cruise ships. And the vacation on land is even considering flying to a destination, plus the emissions from staying in a hotel, while they didn’t include a flight to the port city in the cruise emissions.

And All the “Smaller” Sustainability Problems

So those were the main environmental problems with cruise ships – dirty sewage, dirty fuel, and lots of ways for cruise ships to break the laws.

I know, it was a lot. But there’s more.

There are lots of sustainability problems with cruising that FOE doesn’t report on:

- Cruise ships causing massive over-tourism in the ports where they stop, totally overwhelming local life while adding very little to the local economy.

- Sweat-shop wages for employees, which cruise companies get away with by being legally registered in countries like Liberia, Panama, and the Bahamas. This is fundamental to cruise companies’ business plans.

- The egregious use of single-use plastics, and illegally dumping that plastic directly into the ocean.

- Food waste from endless buffets and the culture of excess that expects them.

- Engine (in)efficiency.

- And we’ve just barely talked about greenhouse gas emissions from cruise ships. (When climate change isn’t even the biggest environmental problem to discuss in an industry, you know it’s bad.)

Marcie and John both said these are also really important issues, but they’re just much harder to measure. The information simply isn’t available to create a fair grading system for plastics, CO2 emissions, food waste and other problems.

Are Cruise Companies Even Capable of Sustainability Improvements?

I was searching for a silver lining, so I asked John if there were any companies he thought were truly better than the rest. He literally said, “… I’ve just seen too much.” He doesn’t trust any of them.

Still, there are scattered improvements being made in the cruise industry. And just like with airlines, and every other industry, there are huge differences from one company and the next.

But a lot of the improvements in the cruise industry seem more like companies trying to cut costs and look good than meaningfully improve their environmental impact.

(A slimy practice called greenwashing, which I talk about more in this post.)

Some examples: Replacing throw-away shampoo bottles with refillable dispensers. Yes, single-use plastic is totally an issue, but it’s not the biggest problem in the cruise industry – dirty fuel is. But that’s more expensive to fix, and fewer customers know anything about it.

[ Related: Here’s how I avoid buying plastic water bottles – even when traveling in places with unsafe tap water. ]

Or reducing the portion sizes at meals “to reduce food waste.” Yeah, sure – reducing food waste is a bonus. But why should we believe that they’re cutting portions for any reason other than to save money? And where are you sourcing your food? Is it organic? Is it locally sourced?

Win-win improvements are great. And people and brands deserve to do well for doing good. (That’s why I write so many reviews of sustainable brands – to help you find the good ones.)

But the majority of cruise companies only make the changes that save money, and skip the ones that cost money – but which would do the most good for the environment.

It’s clear that they’re not the ones pushing the envelope and innovating on sustainability. They’re dragging their feet and only doing what they’re absolutely forced to do.

Nice article, Ketti. But I have one bone to pick.

Sustainability is not “a spectrum.” at least for most of the products and services we are exposed to or use. The United Nations relies on its 1987 Brundtland Commission definition (reinforced at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit) of sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Therefore sustainability is binary: either the definition is satisfied or it isn’t.

If there is a spectrum of sustainability, it is among a set of like things all of which satisfy the UN/Brundtland sustainability definition and in which some of those things are less impactful or less demanding of resources than the others.

In contrast, among things that fail the UN/Brundtland binary standard, it is incorrect to say that some are more sustainable than others because none of them are sustainable.

Does that make sense? (See e.g.: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability)

Hi Larry,

Thank you for getting in touch!

Yes, I totally understand what you’re saying and I’m familiar with the UN definition. But a definition that works for the UN doesn’t necessarily work for the vast majority of normal people, who have to start somewhere.

Perhaps what I should have said is that living more sustainably is a journey. And if all we do is tell people they’ve failed, instead of that they’re getting closer, it will shut them down and not be productive. I believe that, while educating on what would be ideal, we have to give alternatives that are better than the status quo, even if they aren’t perfect, in order to encourage participation instead of overwhelm. (Of course, I’m referring to standards and methods of encouragement that should apply to individuals, not to companies.)

Also, I think we should have some caution in putting so much credence in a definition that is, inherently, short-sighted. How do we know what the needs of future generations will be? All we know is what our needs are today, and we try to apply that with common sense to the future. In the 18th century, I doubt anyone would have guessed that future generations would have wars over black goop buried underground. That’s not to say we should change what we’re aiming for now, or be even more permissive of what we currently consider clearly unsustainable practices, it’s just to point out that I think there’s a need for some degree of flexibility/ recognition of the unknown.

And on the last point, it may be semantics, but I would disagree. “More sustainable” does exist, in the sense of “closer to being sustainable,” less polluting, less wasteful. Again, not perfect, but better. Absolutes are fine for academics and the UN, but I just haven’t seen them translate well into the real world. (Which means, actually, maybe they’re not fine for the UN.)

Thanks again for reading, Larry, and for your thoughtful comment! It made me think, and I very much appreciate it.

Best,

Ketti

Great thoughtful response. The whole issue makes one feel very small.